|

|

Official Journal of the

|

|

|

| Original Article « PDF file » |

|

New Minimally Invasive Surgical Approaches: Transvaginal and Transumbilical

Anibal Wood Branco1; Alcides José Branco Filho2; Rafael William Noda3; Marco Aurélio de George4; Affonso Henrique Leão Alves de Camargo5; William Kondo6

1 Urologist of CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná; 2 General Surgeon of CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná; 3 General Surgeon e Endoscopist of CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná; 4 General Surgeon of CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná; 5 Urologist of CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná; 6 General Surgeon do CEVIP (Advanced Center of Videolaparoscopy of Paraná), Curitiba - Paraná.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Since the advent of laparoscopy, surgical techniques have been changing in an attempt to reduce

patient's morbidity, thus less invasive procedures have been used. The aim of this manuscript is to report our experience

in regard to two new minimally invasive surgeries approaches, i.e., the transumbilical laparoscopic surgery (TLS)

and the natural orifices transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Patients and Methods: Three periumbilical

trocars have been used to perform transumbilical laparoscopic surgery. At completion of the procedure, all three port

incisions were united and the specimen was retrieved from the abdominal cavity. NOTES was performed through

transvaginal access. After opening the vaginal mucosa in the posterior cul-de-sac, a double-channel flexible endoscope

was inserted into the abdominal cavity. One or two additional trocars were placed (hybrid technique) to control

the pneumoperitoneum and to mobilize intrabdominal structures. Once the procedure was finished, the specimen

was retrieved through the vagina. Results: Eight procedures were performed using the previously described

techniques, including 3 cholecystectomies by TLS, 3 cholecystectomies by NOTES, 1 nephrectomy by TLS, and 1 nephrectomy

by NOTES, with mean operative time of 40.3, 63, 171.6 and 170 minutes, respectively. Difficulty in handling the

flexible endoscope in NOTES and intra and extra-abdominal instrument collision in TLS were the two intraoperative

incidents observed. Conclusions: These new techniques are feasible; however prospective clinical studies are still

necessary to confirm their real indications and benefits.

Key words: minimally invasive surgery, NOTES, transumbilical, cholecystectomy, nephrectomy.

Bras. J. Video-Sur, 2008, v. 1, n. 1: 029-036

| Accepted after revision: February, 07, 2008. |

INTRODUCTION

volution is part of Medicine; however, it is not

always easily accepted among physicians. In

the last decades surgical specialties have been experimenting advances and changes, thus even

more minimally invasive techniques have been adopted

to reduce patient's morbidity.

Since the initial description of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 1987 by

Mouret1 this evolution process has started. In spite of its steep learning

curve, different surgical specialties have already

adopted this minimally invasive approach as a

standard technique2-3, which resulted in reduced

postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, earlier

postoperative recovery and better cosmetic

results4-8.

Recent laparoscopic surgical advances have been associated to the reduced size

and number of ports to reach the objective of a minimally invasive

surgery9-14. In the literature there are an increase number of reports

regarding the adoption of transumbilical approach

to perform cholecystectomies12,

oophorectomies13,

appendectomies14 and

nephrectomies9,10.

The most epic evolution of this continuous development process is the Natural

Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES). It is

a new approach accessing without an incision the

abdominal cavity ("scarless surgery") having

natural orifices as the entry point to the abdomen,

i.e., transgatric, transvaginal, transvesical or

transcolonic access of the intra-abdominals organs through

the insertion of an endoscope into the peritoneal

cavity15. Therefore, without the incisions in the abdominal

wall surgical traumas would decrease even more. The

first report of this surgical technique was by Gettman

and cols. 16 in 2002, which depicted the feasibility

of transvaginal nephrectomies in an experimental

model at Texas University. Two years later, Kalloo e

cols. 17 performed transgastric hepatic biopsy at

Johns Hopkins University. After those initial reports

other researchers depicted the safety of transgastric

access to ligation of fallopian tubes18,

cholecystectomy19, cholecystogastric

anastomosis19,

gastrojejunostomy20, partial hysterectomy with

oophorectomy21,22,

splenectomy23, gastric

reduction24, nephrectomy25

and pancreatectomy26 , all of them based on

experimental studies in a porcine model. Since 2007, some

surgeons have performed

cholecystectomies27-32 and

nephrectomies33 by means of a transvaginal route

in human beings.

The objective of this manuscript is to present our clinical experience with these

new minimally invasive approaches.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Instruments For Transumbilical Surgery

Basic laparoscopy instruments have been used to perform transumbilical surgeries.

Although some authors have already reported the use

of articulated laparoscopic10, staplers,

magnetic positioning of intra-abdominal cameras,

robotic prototypes11,34, in our experience the use of

these special instruments are not essential.

Surgical Team and Instruments for Notes

It is suggested that NOTES should be performed by a multidisciplinary team with at

least general surgeons and endoscopists, as it is a

surgical technique still being studied. A highly skilled team

in advanced laparoscopic surgery is required;

therefore in case of complications the surgery could be

promptly converted to laparoscopy.

The basic instruments to perform transluminal endoscopic surgeries include:

· double channel flexible endoscope (Karl Storz Endoskopi, Germany);

· hook knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan);

· needle knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan);

· hot biopsy forceps (Boston Scientific,

Natick, MA, USA);

· endoscopic clips (Clip Fixing Device, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan);

· grasping forceps (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan);

Transumbilical Access Surgical Technique

Patient should be placed in a position in the operating table accordingly to the surgical

procedure to be performed. After induction of

general anesthesia an oral-gastric tube is placed to

aspirate the stomach contents. Through the umbilicus

the Veress needle is inserted (Figure1A), thus

allowing the influx of carbon dioxide. Then

pneumoperitoneum is established and intra-abdominal pressure

is maintained between 12 and14 mmHg. A 10mm trocar for a

30o optic is inserted into the

periumbilical region, followed by two additional trocars (5mm

or 10mm) placed adjacent to the primary trocar. Therefore, we have two trocars to perform

the planned procedure (Figures 1B, 1C e 2).

|

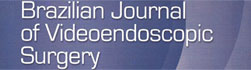

Figure 1 - Transumbilical Laparoscopic Nephrectomy.

(A) Transumbilical Veress Needle placement for insufflation of

abdominal cavity. (B) Periumbilical trocars placement. (C)

External manipulation of instruments (D) Final aspect of the surgery. |

|

Figure 2 - Placement of trocars for transumbilical

laparoscopic cholecystectomy. |

At completion of the surgery, the specimen is placed into an endobag which is held with

a grasping forceps. The three trocars are removed

and the ports incisions are sutured (Figure 3A).

Then, the orifice in the aponeurosis is enlarged and

the endobag is easily retrieved from the abdominal cavity. In case of a cholecystectomy the

gallbladder is directly removed without the use of an

endobag (Figures 3B and 3C). Very large specimens

are removed by morcellation. Figures 1D and 3D depicted the surgery final aspect.

|

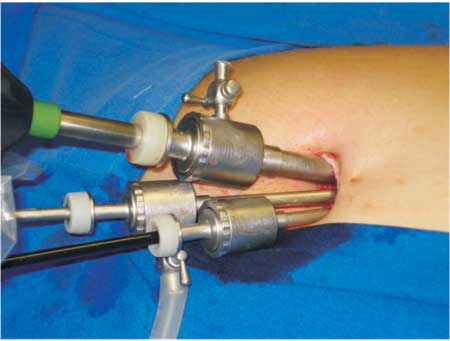

Figure 3 - Transumbilical Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy.

(A) Approximation of the skin incision. (B e C) Gallbladder

removal through the umbilicus. (D) Final aspect of the

transumbilical incision in lambda form. |

Transvaginal Access Surgical Technique in Human Beings

Preoperative preparation of the patient

includes bowel preparation with fleet enema the night

before and 8 hours fasting. One hour prior to the surgery

vaginal embrocation with povidone-iodine is performed.

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with patient placed in litothomy

position, legs supported by padded obstetric leg holders

and arms fastened along the body. Then, nasogastric

and vesical probe are placed. During the induction of

the anesthesia a prophylactic antibiotic (cefazoline 1g)

is administered. Povidine-iodine is used for cleansing

the operative field, and another vaginal embrocation

is performed with this solution.

A Sims speculum is inserted into the vagina and the cervix is grasped with a Pozzi forceps in

its posterior lip, then two Breisky retractors (one

posterior and one lateral) are used to expose the

structures. So, anterior traction of the cervix is performed to

stretch the posterior fornix, and the vaginal mucosa in

the posterior cul-de-sac is opened at the vaginal

cervix junction by a 2,5cm smile incision. After that, the

posterior margin is clamped with an Allis forceps and

with the index finger blunt dissection is

performed. Peritoneum of the posterior cul-de-sac is then

identified and opened.

Flexible endoscope is inserted into the peritoneal cavity and gas is insufflated to

establish pneumoperitoneum (Figure4A). A 5mm umbilical

trocar is used to control the abdominal pressure (12 a

14 mmHg) and to insert a clamp to mobilize the

abdominal structures (hybrid

technique)32. Another 5mm trocar may be placed depending on the

procedure33. (Figure 4D). Then proceed to endoscopic retro vision

to visualize the endoscope exact entry point in the

pouch of Douglas (Figure 4B). Then the endoscope is

moved forward into the abdominal cavity and

surgical procedure is performed (Figure 4C). At

completion of the surgery, the surgical specimen is retrieved

from the abdominal cavity with a polypectomy snare

(Figure 9) (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

|

Figure 4 - Hybride Transvaginal NOTES. (A)

Laparoscopic visualization of the posterior cul-de-sac opening to vaginal

access in transvaginal hybrid nephrectomy. (B) View after

endoscope insertion through transvaginal route in transvaginal

hybrid cholecystectomy.(C) External manipulation of the endoscope

after insertion into the abdominal cavity. (D) Transvaginal

hybrid nephrectomy with two accessory ports. |

|

Figure 9 - (A) Gallbladder removal with a polypectomy

snare after transvaginal hybrid cholecystectomy. (B) Kidney

prehension with polypectomy snare for retrieval from the abdominal

cavity after transvaginal hybrid nephrectomy. |

After reviewing the peritoneal cavity haemostasis, the pneumoperitoneum is deflated

and the cul-de-sac is closed with continuous suture of

2-0 chromic catgut or 2-0 vicryl.

RESULTS

From July 2007 until January 2008, one of the two approaches above described were performed

in eight patients submitted to surgery. Subsequently

we described the intraoperative details of each technique.

Transumbilical Approach

Until now we performed three transumbilical cholecystecytomy (Figures 5A,5B,5C e 5D) and

one transumbilical nephrectomy in our service. All cholecystectomis were performed with two 5

mm trocars (one to the optical trocar) and one 10mm

trocar. In fact, in the first case three trocars were

being used until the identification and isolation of artery

and the cystic duct; however, we had to substitute one

of the 5 mm trocar by a 10 mm due to technical

difficulties to place the clips using a 5mm clamp. Although

during 20 minutes we attempted to apply the 5mm

clamps, the operative time was 56 minutes. In the two

following cases a 10mm trocar was used since the beginning

of the surgery; therefore, the procedures last 30 and

35 minutes, respectively.

|

Figure 5 - Transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

(A) Release of the adhesions around the gallbladder (B) Cystic

duct dissection (C) Duct and cystic artery isolation. (D) Cystic

duct section after clips placement. |

There were no complications in the nephrectomy; thus special articulated

laparoscopic instruments were not necessary (Figure 6 and 7).

Two 5mm trocar and one 10 mm trocar for a 30o

optical were used. The procedure was performed in

63 minutes, and estimated bleeding was 50ml.

|

Figure 6 - Transumbilical nephrectomy. (A) Colon

medial mobilization. (B e C) Identification and dissection of the

ureter. (D) Gonadal vein ligature. |

|

Figure 7 - Transumbilical Laparoscopic Nephrectomy. (A)

Left renal artery ligation with Hem-o-lok. (B) Left renal vein

dissection. (C) Left renal vein ligation with Hem-o-lok. (D) Placement

of Hem-o-lok into the ureter. |

All postoperative patients had a good evolution, and they were discharged from hospital

on the first day after surgery.

Transvaginal Notes

Four patients were successfully submitted to transvaginal hybrid surgery, 3 cholecystectomies

and one nephrectomy.

In the cholecystectomies to control the pneumoperitoneum and the gallbladder mobilization

a 5mm transumbilical accessory puncture was performed. None of the cases presented

intra-operative bleeding (Figures 8A and 8B).

Incidents happened due to the inexperience in handling

the flexible endoscope to perform the surgery. The operative time of the three cholecystectomies

was 150,270 and 95 minutes, respectively. Patients did

not present any intraoperative complications and all

of them were discharged from hospital on the first postoperative day.

|

Figure 8 - Hybrid transvaginal NOTES Cholecystectomy.

(A) Cystic duct dissection. (B) Dissection of the gallbladder from

the hepatic bed with a hook knife. |

Two 5mm abdominal accessory trocars were placed, one transumbilical and another

subxiphoid during nephrectomy. Operative time was 170

minutes and estimated bleeding was 350ml.

On the morning day after surgery four patients received a regular diet and on the

first postoperative day they were discharged from

hospital. Analgesia required only ordinary

analgesic (dipirone) to relieve pain in all cases.

Postoperatively patients were oriented to restart sexual activity after 40 days.

DISCUSSION

With the advent and rapid revolutionary evolution of laparoscopic surgery all over

the world in 1990's decade, unquestionable

advantages over open surgery are evident: as less postoperative pain, cosmetic surgery, short

length of hospital stay, quick pulmonary recovery

and prompt return to work.

Nevertheless, experimental and clinical researches are still searching for new

minimally invasive surgical techniques and approaches.

New procedures to improve postoperative recovery

and reduce risks have been arising everyday in the

world literature as a way to overcome the

laparoscopic approaches results.

Enlargement of port site or an additional port is frequently necessary to remove

specimen. Depending on the procedure performed at

surgery completion patients usually have 3 to 6 incisions

about 1 to 4 centimeters long. Laparoscopy incisions

potential morbidity include: worst cosmetic results,

cutaneous innervations injury, chronic pain, subcutaneous

bleeding and development of incisional

hernia10.

In order to spare patients from morbidity associated to incisions, some techniques such

as morcellation, transvaginal extraction of the

surgical specimen, natural orifices surgery and

transumbilical surgery have been developed to reduce the

number of incisions and/or remove the surgical specimen

after laparoscopic procedure.

As a way to reduce the above mentioned

morbidity35-40 morcellation of specimens have

been performed in some institutions; however, this

approach has a negative impact as the specimen can not

be evaluated for pathological staging41, limiting its use

with malignant tumors.

Traditionally gynecologists used transvaginal route to performed procedures such

as hysterectomies42,

adnexectomy43, tubal

ligation44 and others. In addition to that many authors have

already described vaginal removal of surgical specimens

after gynecological laparoscopies45-49

. Transvaginal access has already been used to remove surgical

specimens after laparoscopic procedures even by some

general surgeons and urologists. Extraction of

surgical specimens from the abdominal cavity is a

feasible approach; however unfortunately it can only

be performed in female patients.

Recently, the Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) - a new

revolutionary concept of minimally invasive surgery has

attracted surgeons and endoscopists. The three

main justifications for NOTES are improved

cosmetic appearance, easy access, and the concept that

human ability and technological advance can continue

to reduce patients' trauma and discomfort, and

maintain surgery effectiveness 55.

NOTES is a less invasive procedure as well as laparoscopy; therefore it is an alternative

technique to open surgery as it can reduce postoperative

stress, morbidity and hospital length stay. Moreover,

NOTES has a theoretically potential to reduce risk

of complications such as wounds infections,

postoperative hernia and adhesions17-19. An additional advantage

of this approach is that it could be performed in

patients with extensive scars, serious burns, infection of

the abdominal wall and morbid obesity, besides the

high risk and critically ill patients56. In this manuscript

we report four successful cases of hybrid

transvaginal NOTES. Difficulty in handling the flexible

endoscope and manipulating instruments to perform basic

surgical maneuvers can be explained by our

procedures operative time. Although we believe learning

curve data should be evaluated as it is in laparoscopy;

due to our small sample it was not possible to be

evaluated. In our opinion, transvaginal endoscopic

surgery benefits are scientifically acknowledged, thus it

will not cause an additional risk of postoperative

fistulae in patients (transgastric, transcolonic and

transvesical access).

Transumbilical surgery is an alternative technique to traditional laparoscopy with an

improved cosmetic result due to the periumbilical

incision. Moreover, comparing to NOTES it has a short

learning curve because the anatomic visualization is almost

the same to the traditional laparoscopy what changes

is the puncture site10. The four reported cases

were successfully performed without difficulties. As

trocars were placed into the periumblical region, they

were jointed through elliptical incision to remove the

surgical specimen. As we did not have any

articulated instrument intra and extra-abdominal collision

were the only intraoperative incident regarding trocars.

One kidney and three gallbladders were removed from

the abdominal cavity, without morcellation.

CONCLUSIONS

Any new technology should be carefully used with human beings. Until the present moment only a few cases were reported in the literature. The development of new endoscopic tools and accessories certainly will accelerate the development of NOTES technique and improve its results; therefore in the future it may become an acceptable alternative technique and a preferable access route for some special abdominopelvic conditions in well selected patients. Transumbilical laparoscopic surgery is a feasible technique, as it is similar to traditional laparoscopy, except for the position of the trocars. Proposed benefits and safety of both surgical techniques still need to be depicted in further clinical studies comparing the two techniques to traditional techniques.

REFERENCES

1. Mouret P. From the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy

to the frontiers of laparoscopic surgery; the future

prospective. Dig Surg 1991; 8: 124-5.

2. Kondo W, Garcia MJ, Ivano FH, Bahten LCV, Miyake

RT, Smaniotto B. Curva de aprendizado na

fundoplicatura laparoscópica durante a residência médica em cirurgia

geral. Rev Col Bras Cir 2006; 33: 96-100.

3. Peterli R, Herzog U, Schuppisser JP, Ackermann C,

Tondelli P. The learning curve of laparoscopic cholecystectomy

and changes in indications: one institutions's experience

with 2,650 cholecystectomies. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech

A 2000; 10: 13-9.

4. Branco AW, Branco Filho AJ, Kondo W, George MA,

Maciel RF, Garcia MJ. Hand-assisted right laparoscopic live

donor nephrectomy. Int Braz J Urol 2005; 31: 421-9.

5. Kondo W, Rangel M, Tirapelle RA, Garcia MJ, Bahten

LCV, Laux GL, et al. Emprego da laparoscopia em mulheres

com dor abdominal aguda. Rev Bras Videocir 2006; 4: 3-8.

6. Ortega AE, Hunter JG, Peters JH, Swanstrom LL,

Schirmer B. A prospective, randomized comparison of

laparoscopic appendectomy with open appendectomy.

Laparoscopic Appendectomy Study Group. Am J Surg 1995; 169:

208-12.

7. Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S. Laparoscopic surgery for

morbid obesity. Surg Clin North Am 2001; 81: 1145-79.

8. Topçu O, Karakayali F, Kuzu MA, Ozdemir S, Erverdi

N, Elhan A, et al. Comparison of long-term quality of life

after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc

2003; 17: 291-5.

9. Desai MM, Rao PP, Aron M, Pascal-Haber G, Desai

MR, Mishra S, et al. Scarless single port

transumbilical nephrectomy and pyeloplasty: first clinical report. BJU

Int 2008; 101: 83-8.

10. Raman JD, Bensalah K, Bagrodia A, Stern JM, Cadeddu

JA. Laboratory and clinical development of single keyhole

umbilical nephrectomy. Urology 2007; 70: 1039-42.

11. Zeltser IS, Bergs R, Fernandez R, Baker L, Eberhart

R, Cadeddu JA. Single trocar laparoscopic nephrectomy

using magnetic anchoring and guidance system in the porcine

model. J Urol 2007; 178: 288-91.

12. Cuesta MA, Berends F, Veenhof AA. The

"invisible cholecystectomy": A transumbilical laparoscopic

operation without a scar. Surg Endosc 2007; Oct 18.

13. Lin JY, Lee ZF, Chang YT. Transumbilical management

for neonatal ovarian cysts. J Pediatr Surg 2007; 42: 2136-9.

14. Martínez AP, Bermejo MA, Cortœ JC, Orayen CG,

Chacón JP, Bravo LB. Appendectomy with a single trocar

through the umbilicus: results of our series and a cost

approximation. Cir Pediatr 2007; 20: 10-4.

15. de la Fuente SG, Demaria EJ, Reynolds JD, Portenier

DD, Pryor AD. New developments in surgery: Natural

Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES). Arch Surg

2007; 142: 295-7.

16. Gettman MT, Lotan Y, Napper CA, Cadeddu

JA. Transvaginal laparoscopic nephrectomy: development

and feasibility in the porcine model. Urology 2002; 59: 446-50.

17. Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath SB, Niiyama H, Hill

SL, Vaughn CA, et al. Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a

novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in

the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 114-7.

18. Jagannath SB, Kantsevoy SV, Vaughn CA, Chung SS,

Cotton PB, Gostout CJ, et al. Peroral transgastric endoscopic

ligation of fallopian tubes with long-term survival in a porcine

model. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61: 449-53.

19. Park PO, Bergström M, Ikeda K, Fritscher-Ravens A,

Swain P. Experimental studies of transgastric gallbladder

surgery: cholecystectomy and cholecystogastric anastomosis

(videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61: 601-6.

20. Kantsevoy SV, Jagannath SB, Niiyama H, Chung SS,

Cotton PB, Gostout CJ, et al. Endoscopic gastrojejunostomy

with survival in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;

62: 287-92.

21. Wagh MS, Merrifield BF, Thompson CC.

Endoscopic transgastric abdominal exploration and organ resection:

initial experience in a porcine model. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2005; 3: 892-6.

22. Wagh MS, Merrifield BF, Thompson CC. Survival

studies after endoscopic transgastric oophorectomy and

tubectomy in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63: 473-8.

23. Kantsevoy SV, Hu B, Jagannath SB, Vaughn CA,

Beitler DM, Chung SS, et al. Transgastric endoscopic

splenectomy: is it possible? Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 522-5.

24. Kantsevoy SV, Hu B, Jagannath SB, Isakovich NV,

Chung SS, Cotton PB, et al. Technical feasibility of

endoscopic gastric reduction: a pilot study in a porcine

model. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 65: 510-3.

25. Lima E, Rolanda C, Pêgo JM, Henriques-Coelho T, Silva

D, Osório L, et al. Third-generation nephrectomy by

natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. J Urol 2007;

178: 2648-54.

26. Matthes K, Yusuf TE, Willingham FF, Mino-Kenudson

M, Rattner DW, Brugge WR. Feasibility of

endoscopic transgastric distal pancreatectomy in a porcine animal

model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Oct;66(4):762-6.

27. Marescaux J, Dallemagne B, Perretta S, Wattiez A, Mutter

D, Coumaros D. Surgery without scars: report of

transluminal cholecystectomy in a human being. Arch Surg 2007; 142: 823-6.

28. Zorron R, Maggioni LC, Pombo L, Oliveira AL, Carvalho

GL, Filgueiras M. NOTES transvaginal

cholecystectomy: preliminary clinical application. Surg Endosc 2008; 22: 542-7.

29. Zorrón R, Filgueiras M, Maggioni LC, Pombo L,

Lopes Carvalho G, Lacerda Oliveira A. NOTES.

Transvaginal cholecystectomy: report of the first case. Surg Innov

2007; 14: 279-83.

30. Zornig C, Emmermann A, von Waldenfels HA, Mofid

H. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy without visible

scar: combined transvaginal and transumbilical

approach. Endoscopy 2007; 39: 913-5.

31. Bessler M, Stevens PD, Milone L, Parikh M, Fowler

D. Transvaginal laparoscopically assisted

endoscopic cholecystectomy: a hybrid approach to natural

orifice surgery. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66: 1243-5.

32. Branco Filho AJ, Noda RW, Kondo W, Kawahara

N, Rangel M, Branco AW. Initial experience with

hybrid transvaginal cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc

2007; 66: 1245-8.

33. Branco AW, Filho AJ, Kondo W, Noda RW, Kawahara

N, Camargo AA, et al. Hybrid Transvaginal Nephrectomy.

Eur Urol 2007; Nov 5.

34. Park S, Bergs RA, Eberhart R, Baker L, Fernandez R,

Cadeddu JA. Trocar-less instrumentation for laparoscopy:

magnetic positioning of intra-abdominal camera and retractor. Ann

Surg 2007; 245: 379-84.

35. Urban DA, Kerbl K, McDougall EM, Stone AM,

Fadden PT, Clayman RV. Organ entrapment and renal

morcellation: permeability studies. J Urol 1993; 150: 1792-4.

36. Landman J, Venkatesh R, Kibel A, Vanlangendonck

R. Modified renal morcellation for renal cell

carcinoma: laboratory experience and early clinical application.

Urology 2003; 62: 632-4.

37. Camargo AH, Rubenstein JN, Ershoff BD, Meng MV,

Kane CJ, Stoller ML. The effect of kidney morcellation

on operative time, incision complications, and

postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic nephrectomy. Int Braz J

Urol 2006; 32: 273-9.

38. Varkarakis I, Rha K, Hernandez F, Kavoussi LR,

Jarrett TW. Laparoscopic specimen extraction: morcellation.

BJU Int 2005; 95: 27-31.

39. Greene AK, Hodin RA. Laparoscopic splenectomy for

massive splenomegaly using a Lahey bag. Am J Surg 2001; 181:

543-6.

40. Bojahr B, Raatz D, Schonleber G, Abri C, Ohlinger

R. Perioperative complication rate in 1706 patients after

a standardized laparoscopic supracervical

hysterectomy technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2006; 13: 183-9.

41. Kaouk JH, Gill IS. Laparoscopic radical

nephrectomy: morcellate or leave intact? Leave intact. Rev Urol 2002;

4: 38-42.

42. Figueiredo O, Figueiredo EG, Figueiredo PG, Pelosi

MA 3rd, Pelosi MA. Vaginal removal of the benign

nonprolapsed uterus: experience with 300 consecutive operations.

Obstet Gynecol 1999; 94: 348-51.

43. Sahin Y. Vaginal hysterectomy and oophorectomy in

women with 12-20 weeks' size uterus. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand 2007; 86: 1359-69.

44. Hartfield VJ. Female sterilization by the vaginal route:

a positive reassessment and comparison of 4 tubal

occlusion methods. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1993; 33:408-12.

45. Blecharz A, Rzempo³uch J, Zam³yñski J.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy with vaginal extraction. Ginekol Pol 1994;

65: 477-81.

46. Ghezzi F, Raio L, Mueller MD, Gyr T, Buttarelli M,

Franchi M. Vaginal extraction of pelvic masses following

operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 2002; 16: 1691-6.

47. Jadoul P, Feyaerts A, Squifflet J, Donnez J.

Combined laparoscopic and vaginal approach for

nephrectomy, ureterectomy, and removal of a large

rectovaginal endometriotic nodule causing loss of renal function. J

Minim Invasive Gynecol 2007; 14: 256-9.

48. Pardi G, Carminati R, Ferrari MM, Ferrazzi E, Bulfoni

G, Marcozzi S. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal removal

of ovarian dermoid cysts. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 85: 129-32.

49. Spuhler SC, Sauthier PG, Chardonnens EG, De Grandi P.

A new vaginal extractor for laparoscopic surgery. J Am

Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994; 1: 401-4.

50. Breitenstein S, Dedes KJ, Bramkamp M, Hess T,

Decurtins M, Clavien PA. Synchronous laparoscopic sigmoid

resection and hysterectomy with transvaginal specimen removal.

J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2006; 16: 286-9.

51. Vereczkei A, Illenyi L, Arany A, Szabo Z, Toth L,

Horváth OP. Transvaginal extraction of the laparoscopically

removed spleen. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 157.

52. Zornig C, Emmermann A, von Waldenfels HA,

Felixmüller C. Colpotomy for specimen removal in laparoscopic

surgery. Chirurg 1994; 65: 883-5.

53. Gill IS, Cherullo EE, Meraney AM, Borsuk F, Murphy

DP, Falcone T. Vaginal extraction of the intact specimen

following laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. J Urol 2002; 167:

238-41.

54. Yuan LH, Chung HJ, Chen KK. Laparoscopic

radical cystectomy combined with bilateral nephroureterectomy

and specimen extraction through the vagina. J Chin Med

Assoc 2007; 70: 260-1.

55. Swain P. A justification for NOTES _ natural

orifice translumenal endosurgery. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;

65: 514-6.

56. Inui K. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery:

a step toward clinical implementation? Gastrointest

Endosc 2007; 65: 694-5.

Correspondence address:

William Kondo

Address: Av. Getúlio Vargas, 3163 ap. 21

CEP 80240-041

Curitiba - Paraná

E-mail: williamkondo@yahoo.com